The Great Community Radio Switch On

“Community based broadcasting, where local people produce and present their own programmes, promises to be the most important new cultural development in the United Kingdom for many years.”

“Community based broadcasting, where local people produce and present their own programmes, promises to be the most important new cultural development in the United Kingdom for many years.”

Professor Anthony Everitt, March 2003

Contents:

- Why Start a Community Radio Station?

- What Is Community Radio?

- A Brief History of Community Radio

- Defining Your Approach

- ‘Community’ vs ‘Radio’

- Community Radio and Social Gain

- Ofcom

- The Community Media Association

Why start a community radio station?

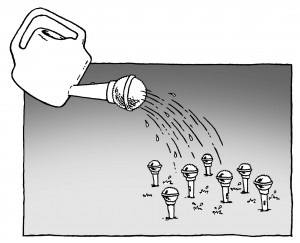

Before another word is said, we should warn you: Community radio will get into your blood. It may well stay there like an exotic parasitic disease, an itch to be constantly scratched. It may sap every last drop of your energy, wake you up in the middle of the night, drag you out of bed and turn your hair grey. So why on earth should anyone do it?

We think you should do it because it can enable your community to change itself, to connect with itself, to realise its full potential.

We think you should do it because it is extraordinary fun. It is extraordinarily satisfying not just to make radio like no-one else is making, but to help transform your community itself while you do it.

CRIB SHEET

Why start a community radio station?

- Because you can.

We think you should do it to express yourself and to fulfil yourself. To empower yourself and engage yourself. Do it for the memories, do it for the fun. Do it for the look on people’s faces when you explain it to them and they say ‘wow!’ Do it for the thrill of flying by your bootstraps, for the rawness, the immediacy, the buzz.

Community radio is a venture with the extraordinary capacity to change your life. And like any such extraordinary venture, it can also totally mess up your life.

To even think about setting up a community radio station, you do probably have to be just a little bit nuts. We hope this book will help you keep it like that.

What is community radio?

On Christmas Eve 1906, Reginald Fessenden stood by a microphone in Massachussets to play his violin and read from his bible. It was the first successful audio broadcast and the implications were staggering. Anyone with access to some fairly basic technology had the power to send information, opinion, entertainment and culture directly into people’s homes. Unsurprisingly to some, governments quickly established a firm stranglehold over the airwaves and have kept it pretty tight ever since.

But the magical particles we call radio waves are a glorious gift to the world. Should they be the preserve of state and business? On the streets of the world, activists have claimed their right of access to the airwaves. Community radio has appeared on the front line of revolutionary struggles, with broadcasters literally risking their lives to take their message to their people. It has emerged as unlicensed pirate radio, giving voice to under-represented communities in the estates, barrios and ghettoes of the world.

A very brief history of community radio around the world

Although there are many competing claims, it is widely accepted that the world’s first community radio stations emerged in Bolivia during a tin miners’ strike around 1947. Their trade union decided to use some of the emergency strike fund to pay for 27 local radio stations, offering union members and their families access to the airwaves and opportunities for social benefits – now a familiar formula. It is a measure of the power of the medium that over the next forty years these stations (and others in Latin America) faced regular persecution, arrests of activists and seizure of equipment by authorities.

Meanwhile in California, the Pacifica Foundation set up the USA’s first ‘listener-sponsored’ radio station in 1950 – a variation on community radio that is still the most common model in North America today. From these beginnings, the demand for community radio began to take root around the world. Amid the political radicalism of the 1960s and 70s, community radio activists began lobbying for access to the airwaves across the developed world, both through legal lobbying and less-than-legal broadcasting.

CRIB SHEET

Community radio around the world:

- Has been happening for more than 50 years

- Has emerged in every continent

- Is different everywhere

- But has similarities everywhere

Australia – with its small, dispersed population and little in the way of local commercial or public broadcasting in many areas – began licensing community stations in 1972, and now boasts one of the healthiest community media sectors in the world. In Africa and Asia progress was slower, although stations are now widespread in Southern Africa, Vietnam, India, the Philippines and beyond.

Although the nature of community radio varies considerably from country to country and station to station, some elements are consistent almost everywhere. Community radio, anywhere in the world, is committed to:

- Community development rather than profit

- Providing access to the airwaves to under-represented voices

- Based at grass-roots level and serving a distinct local community·

- Established and run primarily by volunteers and activists rather than paid staff

VOXBOX **

“My advice to anyone getting into community radio would be don’t start from scratch. Look at what is going on in other countries, see how they are doing it. There are years and years of experience internationally, whereas here it is very early days. Listen to their broadcasts, look at their schedules, don’t sit here and feel that there’s nothing to draw on – there is plenty outside the UK.”

Karen Cass, Chair and founder, Radio Reverb, Brighton.

Back in Blighty

The role of pirate broadcasters such as Radio Caroline and Radio Luxembourg in pushing the development of mainstream radio has been well documented. In short, they provided the blueprint (not to mention many of the broadcasters) for BBC Radio 1 and many of the commercial stations we still hear today. These commercially-minded ventures have little to do with community radio as we know it. But much less has been written about smaller, local pirate stations operating in urban areas and around campuses since the 1960s. It was these stations, driven by a love of radio and a perceived need for community broadcasting, that are the true ascendants of modern community radio. As time passed and wisdom accumulated, many activists began to see the advantages to be gained from working alongside, rather than in opposition to the legal broadcasting apparatus. In Britain the drive towards legal recognition was led by the Community Radio Association (now the Community Media Association), formed in 1983 to campaign for a third tier of broadcasting alongside the BBC and commercial stations. The CRA included many veterans of unlicensed stations, plus academics, community activists and other experienced campaigners.

Over the past two decades, the sector has lobbied successive governments and powerbrokers, patiently chipping away at the obstacles and objections. The (then) regulators at The Radio Authority helpfully identified spare pockets of frequencies which could perhaps be used for the purpose. The culmination of these negotiations was contained in The Communications Act 2003 and then the Community Radio Order 2004, which established the final legal framework for full-time, long-term community radio licenses in the UK.

Throughout this process, the British community radio sector, in negotiation with state regulators, has come to a broad consensus about what community radio should actually be. At its simplest, it has two crucial features:

- It is not run for financial profit.

- It is made by a community, for the benefit of that community.

If a station is being run for profit, or it is being imposed upon a community from outside, then it is not a community radio station. Community radio should also serve two principal functions:

- Access: an outlet for cultural, political and artistic voices and opinions which are excluded elsewhere.

- Development: Social, cultural and educational gain for the community as a whole and its individual members.

If a radio station is not offering access to voices which are under-represented elsewhere, and if a station is not of practical benefit to its community, it is not a community radio station.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

FACT BOX 1.01

“Community radio is a new type of radio station focusing on the delivery of specific social benefits to enrich a community or a range of listeners within a small geographical area.”

OFCOM

“Community Radio proposes to be a new tier of very local, not-for-profit (or not profit distributing) radio. It should be different from, and complementary to, existing independent local radio. Community Radio offers potential benefits in terms of social inclusion, local educational, training and experience, and wider access for communities to broadcasting opportunities.”

Department of Culture Media and Sport.

“Community radio shouldn’t be popular, it should be necessary.”

Zane Ibrahim, Bush Radio, Cape Town

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

It should also be emphasised that a community radio station, as we understand it, operates within the law and alongside the authorities. Unlicensed pirate stations can offer access to the marginalised, and can under certain circumstances offer social gain to their community. But it is a sad truth that a radio station cannot ever be sustainable when seizure of equipment and arrest are a daily risk. So to any unlicensed broadcasters reading this we strongly advise getting yourself straight.. The rewards are limitless.

CRIB SHEET

Community radio:

- is legal and licensed

- is made by a community for a community.

- is not for financial profit.

- offers access to the airwaves

- brings social gain

Defining your community and the Radio Regen approach

At its simplest a community is a group of people with an interest in common. That interest could be the area where they live, their religion, age, ethnic origin, lifestyle, hobbies, careers or any combination of the above. The 16 pilot community radio stations which took to the air in 2002 reflected the wide variations in what we can mean by ‘community’ (see below). Old, young, urban, rural, Christian, Muslim, Asian, African-Caribbean and artistic groups were all recognised.

________________________________________________________

FACT BOX 1.02

The Access Radio Pilot Stations, 2002 – 2005

Radio Regen’s projects:

ALL FM – Covered Ardwick, Longsight and Levenshulme in South-Central Manchester. This is an ethnically diverse area of multiple disadvantage, with extensive issues around poverty, poor health, inadequate healthcare, social engagement, crime, drugs and addiction, youth nuisance and gang culture. It is home to a large population of refugees, asylum seekers and recent immigrants from countries such as Somalia and Eastern Europe. A popular slogan at ALL FM is ‘One station, many nations.’ It is also highly socially diverse: extensive literacy problems stand alongside a high population of students and graduates, and the area has strong traditions of small business development, creative involvement and community activism. In its first thirty months, ALL FM brought more than 200 volunteers and 2,000 local guests onto the airwaves. It has more than fifty community partners.

Wythenshawe FM – Covers the Wythenshawe area to the south of Manchester. This huge, sprawling development is one of the largest social housing estates in Europe with a population, including neighbouring districts, of around 90,000. Geographically it is isolated from the rest of Manchester, surrounded by the motorway network, and only seen by most Manchester residents as a signpost on the way to the airport. Ravaged by decades of under-investment and many local families are now experiencing their third generation of adult unemployment. The area has high levels of deprivation on every recognised scale, with notably high rates of disability and chronic illness. Ethnically the community is majority white British, and is notable for strong sense of loyalty to the area and the community felt by residents. The area is also a hot-bed of talent; since going on air WFM has served 200 volunteers, with around 80 active at any given time. 24 are involved in the station soap opera ‘Parkway.’

Other projects:

- Angel Radio (Havant, Hampshire) Aimed at the over-60s in the south coast town.

- Awaz FM (Glasgow) Radio by and for the Asian communities of Glasgow.

- BCB (Bradford) Bradford Community Broadcasting. Service for the diverse communities of Bradford.

- Cross Rhythms City Radio (Stoke on Trent) Community radio from a Christian perspective.

- Desi Radio (Southall, West London) Serving the Panjabi population.

- Forest of Dean Radio (Gloucestershire) Serving a population spread over a large rural area

- GTFM (Pontypridd) a ‘town and gown’ joint project between Glamorgan University and the local residents’ association.

- New Style Radio (Central Birmingham) An African-Caribbean community station.

- Northern Visions Radio (Belfast) Speech-oriented radio for Belfast’s whole community.

- Shine FM (Banbridge, Northern Ireland) – A three-month project operated by a Christian group for the whole community.

- Sound Radio (East London) Catering for the diverse communities of East London.

- Radio Faza (Nottingham) South Asian community station co-managed by the Asian Women’s Project and the Karimia Insititute.

- Resonance FM (Central London) The London Musicians’ Collective run a project of experimental sound and music.

- Takeover Radio (Leicester) A service for children, young people and their families.

Each of the pilots was different and distinct, but broadly they could be categorised in two ways.

- Communities of place.

- Communities of interest.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

As the Fact Box shows, there was a fairly even split between the two models in the pilot scheme, and that probably reflects the debate within the community radio sector as a whole. So let us nail Radio Regen’s colours to the mast. We have established radio stations with geographical communities. The people we represent and serve are those who live within about 5km of our transmitters. We describe our stations as ‘inclusive’ welcoming everyone irrespective of age, race, creed or identity.

It is certain that ‘exclusive’ community radio stations run by communities of interest – religious groups, cultural groups, creative groups etc. – have a natural operational advantage. It is easier to motivate and organise a group who share similar attitudes to a project, and have similar social and cultural values. Community outreach work may be simplified. Management is eased. It’s also easier to market such a station – the brand identity of community of interest is self explanatory e.g. Stamp Collector FM is far easier to explain than ALL FM ‘serving the council wards of Ardwick Longsight & Levenshulme.’ (see below)

We also recognise the wide social gain which can come from apparently ‘exclusive’ stations. Projects such as the excellent Desi Radio, run by the Panjabi community of Southall, or Cross Rhythms, the Christian radio station from Stoke-on-Trent have recorded impressive social and educational benefits. These often stretch well beyond their specified communities. We also accept that the output of these stations can have a significant cultural and artistic value.

Indeed, if frequencies were an unlimited resource, we would urge every club, every faith, every tenants’ association to start their own radio station. The cruel reality is that available frequencies are scarce. If a radio station serving one section of a community is granted a licence, there will not be a frequency available for another radio station which might serve all sections of that community.

So if forced to chose, we support geographically-based community radio stations because they offer the greatest potential benefit to the largest number of people for each available licence. But just as importantly, we have seen the effectiveness of a radio station in bringing sometimes troubled communities together. Community radio is an opportunity to spread tolerance, respect and understanding in a multicultural society. It would be a tragedy if it were to become another point of division, as ‘communities within a community’ scramble against each other for the same prize – a real concern as the sector grows in profile and popularity.

So if forced to chose, we support geographically-based community radio stations because they offer the greatest potential benefit to the largest number of people for each available licence. But just as importantly, we have seen the effectiveness of a radio station in bringing sometimes troubled communities together. Community radio is an opportunity to spread tolerance, respect and understanding in a multicultural society. It would be a tragedy if it were to become another point of division, as ‘communities within a community’ scramble against each other for the same prize – a real concern as the sector grows in profile and popularity.

That said, the knowledge in this manual should apply to all models of community radio. We happily accept that community radio is a broad church and all the healthier for that. Irrespective of our own ideological leanings, we understand that community radio often springs up from other projects or from within communities of interest, with little long-term design. This organic evolution is perhaps as healthy a conception for community radio as any other.

Even defining geographical communities can have problems. ALL FM was established to serve the ‘community’ of Ardwick, Longsight and Levenshulme. These three districts comprise the A6 corridor between central Manchester and Stockport, and from a geographical and administrative perspective this grouping made perfect sense.

ALL FM’s own market research revealed surprising reactions to the brand, however. The residents of Ardwick feel no special connections to the residents of Longsight or Levenshulme, and the same applied to the other districts. Their affinity to the ‘ALL’ brand was strong, but based on the understanding that ‘All FM’ was community radio for ‘all’, not community radio for Ardwick, Longsight and Levenshulme. Similarly, a strong affinity to ALL FM has been recorded among listeners who do not live on the A6 corridor, but in any one of the many nearby districts where the station can be heard and who share many of the socio-economic and cultural characteristics of the area.

ALL FM’s application for a full-time licence from 2005 reflected these findings. The station’s catchment community now matches the reach of its transmitter. Now it truly will be ‘ALL’ FM.

That said, a clearly defined geographical area might not have such difficulties. Community radio for Wythenshawe (WythenshaweFM) is self defining, as it would be for many towns and single neighbourhoods. The issue gets complicated when your particular 10km circle of FM reception doesn’t have a name.

That said, a clearly defined geographical area might not have such difficulties. Community radio for Wythenshawe (WythenshaweFM) is self defining, as it would be for many towns and single neighbourhoods. The issue gets complicated when your particular 10km circle of FM reception doesn’t have a name.

A station will also be defined by its participants. It is vital that you do not fall into the trap of thinking that your community is just the group of people who come in and make radio shows. It is not even those people and their listeners. Do not become just another club. Community radio is too important for that.

You have an obligation to do outreach work, finding sections of the community who are not involved, and involving them. Look to your ethnic and gender mix. As a medium, radio is largely built on big mouths, big egos and expensive gadgets with flashing lights, so of course it mostly attracts boys (of all ages). You may have to take positive action to involve a representative share of women. We had to do exactly this at WythenshaweFM and it’s worked well.

Your station will also be defined by its output. If you have mostly speech you will attract mostly older listeners. If you mostly play classic rock hits all day, you will get a lot of middle-aged men. Volunteers will mostly be attracted to your station by its output, so it makes sense for the output to be as diverse as the community. If a station makes extensive commitments to the elderly, its unlikely to meet them if it is playing hip hop 24 hours a day.

This may seem common sense, but stations will often find themselves torn between the most popular output and the most representative. If you look at the commercial or public sector radio, you will see that all stations aim their output at a specific demographic – an audience of a particular age, social class and range of interest. This is no coincidence. Radio stations of all types have realised that they can reach the largest raw number of listeners that way.

Community radio is different in that it must to some extent try to be all things to all people within that community. If a community radio station tries a formatted, ‘narrowcasting’ approach it will always lose out to the commercial and BBC stations who can do the same thing better. As a result, community radio will never get the biggest audience, nor should it try to. It is not the job of a community radio station to reach the largest number of listeners. However you can be so much more useful to your community if they are actually listening. Striking the balance between giving the audience enough of what they want that they will keep listening, and providing enough variety to keep the loyalty of all your community is an eternal juggling act (see Programming).

CRIB SHEET

Your community:

- can be any group of people with something in common;

- may consist all the residents of a given area, or only those with a shared interest or characteristic;

- is NOT just the people involved in making the radio and their listeners;

- should be reflected in the activities, output, management and personnel at the station;

- needs you.

Thankfully we have found that the best thing to do is often also the right thing to do.

The same applies to your presenters. If you fill your schedules with experienced radio broadcasters who all adhere to the stereotyped “Radio Local” chatter-and-patter microphone techniques, then you have to ask why listeners should choose you over the better-funded, flashier mainstream stations which you are aping. It is our experience that listeners enjoy the rough edges of community radio, the mistakes, the occasional chaos. They also appreciate the apparently random nature of stations which are as diverse, unpredictable and exciting as the communities which spawned them.

So don’t ignore audience figures but don’t fret over them either. If you serve your community, people will come to you.

At the Community FM conference in February 2004, the special guest speaker was Zane Ibrahim, founder of Bush Radio, Cape Town, one of the true heroes in the history of community radio in Southern Africa (more from him shortly). Among many pieces of wise advice, he told the delegates this:

‘Don’t be popular. Be necessary’.

Thankfully, you can be both.

‘Community’ vs ‘Radio’

After addressing the February 2004 Community FM conference, Zane Ibrahim of Bush Radio, Cape Town was taking questions from the floor. One astute questioner asked this: ‘How much of community radio is community, and how much is radio?’

Zane scarcely blinked before replying – to the surprise of some delegates –

‘90% community, 10% radio.’

This is of course a simplification. But it echoes our staff’s experience that resources, energy and time we are devoted overwhelmingly to non-broadcast activity. The volunteers make the radio. It’s the staff’s role to enable them to do it.

VOXBOX **

‘When we set up the full-time stations we thought we knew what we were doing. We knew radio. We’d done a whole bunch of successful RSLs. We thought we could jump in and make great radio.

‘We completely underestimated the need to resource and properly ‘do’ the community side of it. We didn’t set up a radio station, we set up a community centre. By that I mean the needs of the volunteers were nothing to do with radio. We had to go with volunteers to court to stop them being evicted. We had to advise them on the personal issues that were messing up their heads and making them unwelcome in the station.

‘These things are nothing to do with radio but they’re where we had to put priority for our resources – outreach/support as against programme production. We could have the best programmes being made by a small group of skilled volunteers, but if they weren’t representative, if we didn’t have the whole range of the community involved, then it wouldn’t be community radio.’

Phil Korbel, Director, Radio Regen

The relative importance of community against radio also applies to the output. Yes, good output is important. Interesting programming, clever scheduling and skilled presenters are vital ingredients. Some community stations will go so far as to bring in professional presenters to host key shows. That perhaps misses the point. One of the strengths of community radio is that it provides room for error.

If a presenter misfires a jingle or crashes the intro to a song, then that radio is technically imperfect. But what if that presenter is in the studio in spite of health problems, long-term unemployment and depression? While the quality of output might be suffering, if real value and personal development is being added to the volunteer’s life, then that may be a much more important factor. Occasional bad radio is mostly forgotten within moments; good training, support, and life-enhancing opportunities can be remembered for a lifetime.

Of course if the same presenter then goes on to swear, get the station taken off air or loses all your listeners, then that is going too far. As with almost everything in community radio it is a question of finding the right balance.

The 10% : 90% ratio may be very useful as a way of understanding the challenges involved in community radio. But don’t take it too far. Do not attempt to quantify your activities, or count the hours spent on ‘community’ activities as against ‘radio’ activities. Other community stations may find their volunteer base has fewer issues and needs less support off-air. We would however suggest that if your volunteers need little support you’ll deliver more ‘social gain’ – see below -if you seek out those that need some.

Ultimately community radio is what happens when the power of people meets the power of the airwaves. Arguing about which side is more important is like arguing about which hand makes more noise when you are clapping.

CRIB SHEET

Running a community radio station:

- is 90% community, 10% radio;

- may leave you very little time to make radio;

- involves giving volunteers enough rope to tie themselves in knots;

- but not enough to hang themselves.

-

Community radio and social gain

Community radio stations are uniquely placed to make a difference to society. We can deliver skills, boost community pride, boost the community’s image and standing, and improve the delivery of services to those who need them most. We can reach the isolated, the forgotten and the marginalised. We can offer individuals life-changing opportunities and offer the whole community a social hub.

If we can do these things, then we surely must do them, simple morality demands that. And so does the law.

In negotiating its existence with the government, the community radio sector has always been happy to emphasise the development potential of community radio. Before agreeing to license community radio stations, politicians asked (admittedly in a more polite way) ‘so what is in it for us?’ The answer was social gain. This was written into the legislation (Fact Box 1.03) and it is social gain – not brilliant radio or huge audiences – that stations are legally obliged to deliver.

So to a large extent social gain is the bed that the community radio sector has made for ourselves. We should be happy to lie in it. This is not the same as community radio becoming simply another form of paternal public service broadcasting. We must avoid becoming instrumentalised, just another tool of the political authorities. A community radio station must never become ‘Spokesperson FM’ with a succession of official voices telling us to eat up our greens. Community radio is by the people, for the people and of the people, and must always remain so.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

FACT BOX 1.03

Social gain is defined as:

- the provision of radio services to individuals who are otherwise under-served by such services

- the facilitation of discussion and the expression of opinion,

- the provision of education or training

(d) the better understanding of the particular community and the strengthening of links within it

Social gain may also include the achievement of other ‘social objectives’:

(a) the delivery of services provided by local authorities and other public services;

(b) the promotion of economic development and of social enterprises;

(c) the promotion of employment;

(d) the provision of opportunities for the gaining of work experience;

(e) the promotion of social inclusion;

(f) the promotion of cultural and linguistic diversity;

(g) the promotion of civic participation and volunteering.

(adapted from) The Community Radio Order 2004 (HMSO).

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The social gain of a radio station must not only exist – it has to be measurable. It’s not enough to say ‘our radio station has made people happier round here – you can tell from the spring in their step.’ The authorities, from OFCOM to the funding bodies, want cold hard facts: the numbers of people passing through training and so on.

It is also important to explain ‘social gain’ to your station team, staff and volunteers alike. You can be sure that what fires up the vast majority of your volunteers is making radio, not the amazing impact that radio has on the community.

Social gain vs. the world

It is worth noting that the duty to provide real improvements to the community can often come into direct conflict with the right of access to the airwaves – the right which underpins the very foundations of community radio. This is a source of continuing debate within the sector.

To maximise access, a community radio station could have a walk-in, first come, first served policy, where anyone and everyone could book the first available hour to broadcast. Hundreds of different people could access the airwaves every month. The opportunities for creating any kind of identifiable social gain may be minimal. Community radio stations must to some extent restrict access, in order to devote the time and energy to the support and training needed to have a real impact (see box 1.03 above).

CRIB SHEET

The social gain from community radio:

- includes the provision of radio services to the excluded;

- includes public engagement, debate and discussion;

- includes the improvement in the image and self-belief of communities;

- includes the delivery of education and training;

- should also deliver many other social objectives – including access;

- is the principal reason UK community radio exists.

For better or worse, the UK community radio framework is now structured with the emphasis on social gain rather than access. This perhaps places a duty on stations themselves to remember the importance of access. Any community radio station worth its salt will try to get the most social gain while also offering access to voices which do not appear elsewhere on the airwaves.

The pursuit of social gain can also be in conflict with the pursuit of quality broadcasting. Sometimes (although by no means always) the output which brings greatest benefit to an individual or the community is not the output which will bring in most listeners. As always, keep the balance. Ensure that there is easy listening (and we don’t mean the music) elsewhere on the schedule. If you don’t address the needs of the audience, if you don’t entertain the audience, then eventually you are going to lose out.

The Legal Framework

Of all the hurdles and obstacles which face those wishing to establish a community radio station, perhaps the most daunting is the bureaucracy surrounding the license application process. We will guide you through this in detail in Chapter 3, but to set the context, we say this for the first time (of what will be many): The license application form is your friend.

Many of those who are involved in community radio come from a background in pirate radio. Others come from the world of community, political and environmental activism. In both of those worlds the authorities tend to be seen as the enemy – either preventing people from doing what they want to do, or imposing interventions which are not welcome. It can be something of a culture shock to learn that the laws covering community radio were to a large extent drafted according to the wishes of community radio campaigners. These regulations are mostly our own.

Yes, the community radio sector is indeed heavily regulated. To gain a community radio license a group must embark on a complex application process, and make extensive promises about how it will and will not operate. Many of these rules, for

CRIB SHEET

The licensing framework

- was developed with the full co-operation of the community radio sector;

- is your friend;

- can be used as a useful guide;

- is there to protect good community radio stations

example those covering accountability to the community or about the distribution of profits, are there to prevent profit-minded entrepreneurs hijacking the community radio sector to establish a commercial station by the back door.

The regulations are not demanding a surplus on the balance books. They are not demanding a particular share of listenership or any other measures of success used in the mainstream media industry. Instead they are demanding that you hit social gain targets – such as the number of people involved in the station, the number of people trained, the number of community groups and statutory agencies assisted. They are mostly concerned with ensuring that you keep the promises you have made in your licence application.

When you look at individual sections of the license application form, everything it is asking of you should be quite reasonable – covering the activities which you should want to do anyway.. If large sections of it appear utterly irrelevant to what you intend to do, then the problem may not be with the form but with your plans. It may be that what you have in mind is not really a community radio station.

BOX**

One of the most important things about community radio is that it gives everyone the chance to make their voice heard. Some of the people who use it to the greatest effect are using it only sparingly – not permanently, or as an activity in its own right, but as a powerful tool for democracy and change. People such as: – children who do an annual radio project at school and put the questions to their local council that the adults never thought to ask – teenagers who attend a holiday training project, where they learn skills which give them self-respect and help them make something of their lives – young single mothers who learn radio at their local support centre, and who then grow in confidence as they discover how to ask questions and get people in authority to listen to their views – citizens from communities undergoing change who use interviews and documentaries to get a serious hearing for grassroots opinions.

Cathy Aitchison, independent media consultant.

Radio Regen

[a snapshot from 2005 – please see here for current information]

Radio Regen is a registered charity, which was founded in 1999 in Manchester by Phil Korbel, Cathy Brooks and Phil Burgess with this mission: ‘To work with communities to enable them to use community radio to tackle disadvantage.’ Korbel and Brooks were then running the independent radio production company Peterloo Productions, and were looking for a way to move on from making radio with a social conscience, to making radio with a social involvement. The first step, drawing upon a European Social Fund regeneration grant, was establishing a BTEC-accredited radio training course in collaboration with the Manchester College of Arts & Technology (MANCAT).

The graduates of these and many subsequent training courses went on to help establish and run temporary radio stations under RSLs (Restrictive Service Licenses) (see Chapter 2, p.**). At the last count Radio Regen and our trainees have run or helped run 25 radio stations. As the abilities of our trainees have flourished, so has our need to provide ever better training and support. We also soon commence Britain’s first radio production foundation degree course based in community radio.

Radio Regen has also established or been involved in inumerable cultural and developmental projects beyond the strict confines of the radio stations, including the youth project Remix the Streets and the arts project Artransmit, which has established two radio soap operas and run the MCing workshop scheme Beatslam.

The charity has so far enabled more than 5,000 volunteers to get on air, currently employs 23 staff, and has a turnover of around £600,000, making us the largest independent group in the UK community radio sector.

For all that, Radio Regen’s proudest achievement so far has been the establishment of Manchester’s two full-time community radio stations, ALLFM and Wythenshawe FM. When OFCOM granted applications to run pilot access radio stations, Radio Regen was the only group to be awarded two licenses. With those two stations now flying the coop – moving towards long-term security as independent enterprises – Radio Regen is now looking forward to a future at the heart of community radio development in the UK.

In February 2004 Radio Regen organised the first Community FM conference, probably the largest gathering of would-be community radio operators Britain had ever seen. 120 delegates from Aberdeen to the Scilly Isles and from Newry to Norwich,

CRIB SHEET

Radio Regen is:

- a registered community development charity, founded in 1999;

- was the biggest community radio group in Britain;

- organised the Community FM conferences of 2004

- has organised and overseen three separate community radio stations in Manchester;

from all different ages and every imaginable background, ranging from amateur radio enthusiasts through to statutory service providers. The guests included the aforementioned Zane Ibrahim of Bush Radio in South Africa, who described his years as an anti-apartheid guerilla fighter, and how a period of exile in Canada equipped him to establish the first community radio station in Southern Africa. ‘In Africa,’ he told conference, ‘Radio keeps you alive.’

Also present were representatives of OFCOM, and even the Government in the shape of Ivan Lewis, the then Minister for Adult Skills, who left the delegates in no doubt about his faith in community radio at the heart of the national adult skills policy.

Community FM (and its follow up in August, 2005 at which OFCOM regulator Lawrie Hallett helped talk community radio groups through the newly published licence application form) demonstrated the vibrancy, energy and momentum of the community radio sector. It also demonstrated the need for extensive information, education and training for community radio activists and workers.

Radio Regen remains committed to local delivery of community radio services. But our expertise is about to take the national stage.

OFCOM

OFCOM is the Office of Communications, established between 2002 and 2003 as the single regulator for the broadcast media industry. Its duties are wide ranging, but its central statutory duty is to further the interests of citizens and consumers by promoting fair competition and protecting consumers from harm and offensive material.

For those with experience of the five regulatory bodies it replaced (including the Broadcasting Standards Commission and the Radio Authority) OFCOM is a model of clarity and co-operation. Nevertheless it is a huge bureaucracy and can be slow to react. It has been rumoured that OFCOM once commissioned a consultation to establish whether they were having too many consultations. It is theoretically independent of politics, but mostly operates under the watchful eye of the Select Committee for Culture, Media and Sport.

CRIB SHEET

OFCOM is:

- A bit like God, but with less sense of humour

- 😉

OFCOM has the power to grant your license, and the power to revoke it. While it operates according to clearly written guidelines and regulations, its decisions are often marked by your emotional engagement – whether that is anger, sympathy or mercy. It’s rather like a (mostly) benign deity. It grants you the gift of life, it holds great power over you, if you’ve sinned you can even issue prayers and sacrifices in the hope of forgiveness. And of course, it is who you have to account for yourself to at the final whistle.

Our single biggest tip about Ofcom is to talk to them, even if you might have breached regulation. Put yourself in their shoes and see if you feel better about someone ‘coming clean’ or someone obviously trying to evade responsibility for regulatory compliance.

Its community radio website is here and the team can be reached via communityradio@ofcom.org.uk

The Community Media Association

Long before Radio Regen arrived on the scene, the Community Media Association (CMA), formerly the Community Radio Association (CRA), and its members had been campaigning for the rights of communities to generate a third tier of broadcast media, alongside commercial operators and the BBC. The CMA’s head office is in Sheffield, it has a training studio in London and a development office in Scotland.

As a community radio station, you have a basic duty to become actively involved in the CMA for a number of reasons. Firstly because you owe it to them – had it not been for the efforts of the CMA, you would not be on air at all.

Secondly, it is in the interests of every community radio station to bolster and strengthen our collective identity as a sector. The CMA is the only umbrella organisation UK community media has. It is the CMA who will negotiate on your behalf with copyright agencies and the like. The CMA makes sure your views are represented to Parliament, Ofcom, the DCMS and other government departments. It promotes the sector to funders and makes sure community media organisations stand alongside other broadcasters when precious broadcasting resources or new policies are being discussed by government.

Thirdly, the CMA is an invaluable source of experience, wisdom, support and resources. Working with member organisations, it is actively involved in training and advising community radio stations and you would be foolish to miss out. See www.commedia.org.uk for details. The CMA is also working closely with Radio Regen in establishing development resources for the community radio sector.

Activities of the CMA include

- Publishing the community media quarterly newsletter Airflash – full of news, essential information and advice.

- Providing a streaming service (free to organisational members) which enables you to broadcast on the internet as a simulcast or between RSLs.

- Hosting regular conferences and events, perfect for networking and meeting other people with a passion for community radio

- Providing information and advice

- Providing materials for broadcast

- Organising training and research to support the sector

- Representing community media to Government and industry bodies

CRIB SHEET

CMA is:

- Your umbrella organisation

- Your voice in negotiations with authority

- A valuable source of advice and resources

- Still campaigning

- Runs the streaming service Canstream

Finally, while the battle to get community radio on to the air has been (mostly) won, the campaigning work of the CMA is far from finished. As a sector, community radio is possibly just the tip of the community media iceberg. Who knows what still lies beneath the water? You owe it to the next generation of community media activists to keep up the fight.

Hospital Broadcasting Association

Although not community radio by the strict definition, hospital radio shares many of our characteristics – it is generally as a charitable operation by volunteers. The Hospital Broadcasting Association represents around 260 hospital stations, many of which have vast experience in making not-for-profit radio. It is worth checking their website (www.hospitalbroadcasting.co.uk) for details of hospital stations in your area – the possibilities for building friendships and collaboration are wide. Their website is also a useful resource in its own right, with plenty of good, transferable advice.

Radio Academy

The Radio Academy is a charity, formed in 1983 as the professional body for people working in the radio industry and to provide neutral ground on which the whole subject of radio could be discussed. It is dedicated to the encouragement, recognition and promotion of excellence throughout the UK radio industry. Members range from students on relevant courses to Governors of the BBC, and the Academy has embraced the emerging community sector warmly at recent conferences and events.